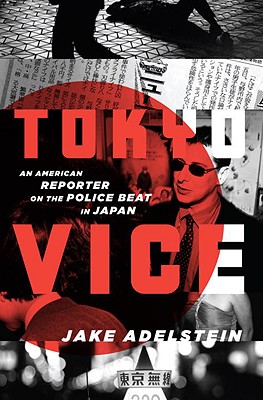

The author holding his book in front of a fuuzoku annaijo

Like any modern metropolis, Tokyo’s glittering skylines carefully conceal a more sinister side from the casual observations of an outsider. And like most other things Japan, organized crime in the form of yakuza carries with it cultural quirks that are at times indecipherable for those of us who live outside the Galápagos. Tokyo Vice by Jake Adelstein is a book that sets out to document and interpret a small slice of this enigma, written from a Jewish-American journalist covering crime stories for the Yomiuri Shinbun. The end result is a thought-provoking page-turner.

I first heard about the book and its author from an episode of The Daily Show last November. Looking at Jake Adelstein’s relaxed demeanour and boyish looks, one would never guess him to be a grizzled veteran reporter well-versed in the workings of the Japanese underworld, but the interview did leave a strong enough impression that I eventually bought a copy of his book. Being the cheap bastard that I am, I of course waited for the paperback release, which is why I am only now writing this review nine months after his Daily Show plug.

I picked up Tokyo Vice without any high expectations. After all, what could a Jewish-American guy possibly manage to uncover about Japan’s crime syndicates, even if he is the first foreign journalist to ever be admitted to the Tokyo Metropolitan Police press club (which is only opened to the Japanese press)? Japan society at large is well-known for its insular nature, much less the secretive yakuza groups with their mystical rituals and honour codes.

As a result, I had expected Tokyo Vice to be a compilation of humorous quirky anecdotes from Adelstein’s time as a reporter there, perhaps only slightly more in-depth and insightful than the typical Japan-is-so-weird drivels that are a dim a dozen at Kinokuniya. There is certainly some fluff of that nature present in Tokyo Vice, but the book is much more personal and serious than that.

The central point behind the book is a record of Adelstein’s journey from an aspiring reporter to a veteran journalist who managed to uncover a huge scoop about how Tadamasa Goto, a then-powerful crime lord in Tokyo, managed to obtain a US visa to receive a liver transplant at UCLA, despite being on ICE‘s blacklist for trafficking and money laundering. The result of his investigation was shunned by the Japanese media, including his own employer the Yomiuri Shinbun, but eventually caught the public’s attention when Los Angeles Times and The Washington Post agreed to publish the story after verifying it with the FBI. He and his family were then put under police protection, while Goto was eventually forced out of his organization (and conveniently became a Buddhist monk while under criminal investigation) as a result of the ensuing scandal. It’s the stuff of TV and movies.

With the popularity of Japanese pop culture, there are many people who dream of studying or working in Japan. But it is actually extremely difficult for a foreigner to enter the Japanese education and corporate systems (which are really one and the same). Most foreigners who do manage to find a living in Japan do so more or less detached from its integrated corporate employment machine (e.g. running a restaurant, working for a foreign MNC, teaching English).

The fact that Adelstein, who is neither Korean nor Chinese (the two foreign groups with the best chance at integration), managed to graduate from Sophia University (one of the top private universities in Japan) and find employment as a full-time Yomiuri Shinbun reporter (a complex process of interviews and standardized testing that only a native can navigate) is a pretty amazing feat by itself. The fact that he managed to not only find a way in but to get to places as an American that even Japanese journalists find difficult accessing is simply unimaginable. The perspective of Japan he offers is nuanced and eye-opening. This is not your typical American travelogue of Japan.

The story that has everything you want from a crime thriller: the murders, the sex, the threats, the corruptions, the battles lost and won. It’s all there, only much more real. Adelstein’s vivd recollection of the many encounters he had has a reporter — with police officers, yakuza bosses, fellow journalists, sex workers — brings his story to life and gives reader a rare matter-of-fact glimpse into a world that, shrouded in the mysticism accorded to it by popular fiction, often seems surreal to those of us living more mundane lives.

Toyko Vice is a hard look at a seldom-seen reality with its share of bitterness and humanity, with the occasional life lesson and a dash of seasoned sentimentality. In a way, it is even inspirational. It is the kind of book that makes me feel that the world out there is a lot bigger than me (and also makes me kind of want to become a journalist.)

Get the book off Amazon or go to Adelstein’s blog Japan Subculture Research Centre for more information.

Thanks for the kind review. I can certainly understand waiting for the paperback edition to come out. Hardbacks are expensive, but they do last a lifetime. Probably actually longer than a lifetime if printed well.

I’m glad that you found something inspiring it. It is very hard to make a living as a journalist; the business model for print journalism is floundering, and investigative journalism is becoming something that people vaguely remember rather than do. But if you’re willing to dedicate yourself to the cause of social justice for lousy pay, terrible working hours, and a lot of meaningless crap that is necessary to do the 5% of the job that actually matters–go for it.

I’m glad I’ve stuck with the work. Sometimes, it makes a difference and it’s as they would say in Buddhist terms, “a right livelihood” . Now if I could just do the other things right, I’d be a saint.

Wow. Didn’t expect you to comment here. Loved your book.

I do agree that the traditional funding behind investigative journalism is drying up with the impending death of printed news, and I can only hope that someone somewhere discovers a new way to fund it in the modern information economy. I suspect it will probably be something similar to how agenda-driven NGOs do things, but perhaps done in a more centralized and objective manner. I suppose we have to wait for this transition period to run its course.

What really inspires me about your book is how you managed to learn so much about things that are hidden out of sight from surface world that we live in. I’m from Singapore, a technocracy that is in many ways similar to Japan when it comes to criminal justice. Things are very well managed here, to the point that reporters here basically have nothing to write about other than official government releases and human interest stories. I cannot imagine any reporter here building up the kind of relationships you have and using them to uncover a story of any social or political significance.

For example, human trafficking in Singapore is very similar to the incident you described in your book (i.e. tourist visa, indentured servitude, deportation upon arrest with no trial), but I’ve not seen any local journalist done a proper research on it before. Journalists here are quasi-government employees and no one dares to stir the hornet’s nest.

I suppose this says more about the quality of local journalism than anything else, but still… I truly admire what you’ve done.